|

|

- Search

| Clin Shoulder Elb > Volume 21(3); 2018 > Article |

Abstract

An intra-articular osteoid osteoma is a very rare cause of elbow pain, and its diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Delayed diagnosis may lead to arthritic change of the joint. In this study, the authors present the occurrence of intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the right elbow of a 15-year-old male patient who presented with prolonged pain and limited motion owing to delayed diagnosis. After confirming the nidus of osteoid osteoma from radiographic evaluation, the lesion was completely removed arthroscopically. The patient presented a complete relief of symptoms and full range of motion. This is the first domestic report of successful arthroscopic treatment of an intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the elbow.

Osteoid osteoma is a well-recognized and relatively common benign bone tumor with characteristic clinical, radiologic, and histologic features. However, juxta-articular and intra-articular osteoid osteomas are rare and considered a separate clinical entity; these tumors rarely present clinical and radiological hallmarks of the classical osteoid osteoma [1]. The occurrence of intraarticular osteoid osteoma in unusual locations results in difficulty in diagnosis. The elbow being a very rare location for intra-articular osteoid osteoma, diagnosis is challenging [2-4]. A confounding factor, such as a previous pediatric supracondylar fracture, may make the diagnosis even more difficult [5], resulting in misdiagnosis of the disease. In this study, the authors present a patient who had suffered from pain and limited motion as a consequence of delayed diagnosis of intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the elbow, which was then successfully treated by arthroscopic excision.

A 15-year-old male patient was referred to Yeungnam University Medical Center for on-going pain and restricted range of motion in the right dominant elbow for 12 months subsequent to a minor trauma, wherein a friend had twisted his arm. Three months after the injury, the patient had visited other institutions and had undergone laboratory and radiologic evaluations. Laboratory evaluation, including a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and blood chemistry profile, did not indicate any rheumatological diseases. Plain radiographs of the affected elbow revealed periarticular osteopenia and periosteal reaction in the distal humeral metaphysis (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed joint effusion with synovial hypertrophy. Signal intensity of the surrounding soft tissue and bone marrow was increased at the distal humerus lateral condyle on T2-weighted coronal images (Fig. 2). The patient was subsequently diagnosed as having bone contusion of the lateral humeral condyle and treated conservatively with intermittent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and splinting. However, the pain and joint stiffness continued to progress. Twelve months after the initial injury, the patient visited our institution. History taking revealed the incidence of continuous pain which could partially be relieved by consuming NSAID and acetaminophen. The flexion-extension arc was limited (100┬░/-40┬░), but both pronation and supination were preserved. Plain radiographs showed increased extensive periosteal reaction with dystrophic calcification as compared to 12 months ago (Fig. 3). Computed tomography (CT) image clearly revealed a 5├Ś3├Ś3-mm-sized calcified nidus in the olecranon fossa (Fig. 4). Sagittal T1-weighted MRI showed marked hypertrophic synovitis with joint effusion and a 6├Ś3.5├Ś3-mm-sized intermediate-low signal intensity nodular lesion in the olecranon fossa (Fig. 5A). T2-weighted image showed a nodular lesion with central intermediate-low signal intensity surrounded by intermediate signal intensity, and a more extensive periosteal reaction in the distal humeral metaphysis as compared to 12 months ago (Fig. 5B). The bone marrow edema (Fig. 5C) was comparatively slightly subsided than 12 months ago (Fig. 2). Bone scan showed increased uptake of tracer diffusely around the right elbow (Fig. 6).

Arthroscopic excision was performed under general anesthesia using the application of a tourniquet, with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. Elbow stiffness was observed under general anesthesia; the forearm was suspended and the elbow was flexed to 90┬░. Initially, a 3.8-mm arthroscope with a visual angle of 30┬░ was introduced through the transtriceps portal to evaluate the posterior compartment. A posterolateral portal was established to enable the introduction of a grasper and curette. Nidus was shown not to cause an impingement in arthroscopy. It was predicted that the range of motion was reduced by joint effusion accompanied by synovitis. Since the nidus was thought to be of the subperiosteal type, the author attempted excision under arthroscopic view. A soft reddish fragment was excised using the grasper and curette under arthroscopic visual control, and the material was sent for histopathologic examination (Fig. 7A). After the nidus was excised using a curette, burring was performed until a normal cancellous bone appeared on the residual bed. A portion of the margin of the sclerotic cortical bone was also removed using a burr (Fig. 7B). However, although the elbow stiffness persisted after removal of the nidus, no capsular release or manipulation was performed in anticipation of improvement. The anterior compartment was evaluated using the standard anteromedial-superior and anterolateral-superior portal. The synovial membrane was hypertrophic with synovitis; the membrane was shaved and joint fluid was slightly dark and xanthochromic. Histopathologic evaluation revealed irregular bone trabeculae in the cellular and vascular stroma with osteoblastic rimming, illustrating features of osteoid osteoma (Fig. 8). The final diagnosis of the lesion was therefore confirmed as osteoid osteoma.

The patient started gentle active exercises 3 days after reduction in the acute pain. Since the joint swelling had improved considerably at 3 weeks, he was encouraged to regain his range of motion. He resumed full range of motion (140┬░/0┬░) at 3 months. At 6 months, the patient resumed his usual activities at full capacity without any pain nor limitations. During the most recent follow-up at 1 year after surgery, the patient remains symptom-free and the Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) was 100, showing significant increase compared to the initial MEPS of 45. The radiographs showed decreased periosteal reaction with elimination of the calcification (Fig. 9). CT confirmed complete removal of the nidus without evidence of recurrence (Fig. 10).

Osteoid osteoma of the elbow is so rare that a study of fourteen patients is the largest reported series from a single institution [4]. Moreover, intra-articular osteoid osteoma of elbow is extremely rare with only few studies being reported before [6]. The diagnosis is compromised due to the atypical entity of clinical and radiographic findings. The clinical manifestations of juxtaarticular and intra-articular osteoid osteoma differ from typical features of osteoid osteoma, resembling common entities such as traumatic or degenerative pathologies of the joint [7]. Pain is not necessarily worse at night, and joint pain may not be relieved by salicylates or NSAID. A variety of nonspecific symptoms such as localized joint swelling, tenderness, decreased range of motion, flexion contractures, muscle atrophy and local warmth may simulate inflammatory arthropathy. Identification of intra-articular tumors on radiography is also difficult because intra-articular tumors are generally medullary or subperiosteal types, presenting the absence or presence of limited sclerosis around the nidus. In addition, the accompanying subtle periosteal reaction and regional osteoporosis may further contribute to the diagnostic confusion [1,4].

It was not until 1947 that Sherman [8] first described osteoid osteoma in the elbow joint and emphasized the relationship of intra-articular osteoid osteoma to osteoarthritic change in the joints. Since then, there have been reports regarding the diagnostic challenges of intra-articular osteoid osteoma in the elbow [4,9]. The reported average duration of symptoms of osteoid osteoma in the elbow before the diagnosis is 19 months [4] which is a long period. Delayed diagnosis of osteoid osteoma in the elbow may lead to serious disturbances of growth during the younger years, leading to permanent impairment of articular function. Confounding factors, such as a previous pediatric supracondylar fracture and history of trauma, may make the diagnosis more difficult [5], resulting in a delayed diagnosis or even misdiagnosis of the disease. The occurrence of symptoms soon after the trauma may lead to a reduced suspicion of osteoid osteoma, as seen in the current case. However, the correlation between trauma and the onset of osteoid osteoma remains unclear. In such cases, a CT scan is the most helpful imaging tool for diagnosis [4]. Orthopedic surgeons should examine for the presence of a nidus to avoid delayed diagnosis which may result in arthritic change of the joint. According to Cotta et al. [2], all patients with osteoid osteoma at the elbow had a periosteal reaction and/or variable cortical thickening on radiologic findings; these findings in elbow bones are associated with the presence of joint effusion.

Treatment of osteoid osteoma involves excision of the tumor including the entire nidus, with further curettage of the perilesional bone. Complete nidus excision is curative and is the most traditional treatment method. Recently, minimally invasive techniques have been exploited as safe and effective alternatives for the treatment of osteoid osteomas, presenting more advantages compared to open excisions; these include reduced postoperative pain, fewer problems associated with wounds, less damage to muscle and ligaments, and a faster return to full activity. Elbow arthroscopy offers a good view of anterior and posterior joint space and the nidus can be precisely excised through the arthroscope, and complete excision of the nidus is essential. At 2 weeks, there was a recurrence of pain, and CT scan confirmed the presence of residual lesion. The patient subsequently had to undergo an open surgery. Use of a shaver makes pathologic diagnosis impossible owing to mechanical artifacts and may therefore be responsible for incomplete excision. Instead of using a shaver, the authors did a complete arthroscopic resection of the nidus using grasper and curette in the current case. The residual bed was then ablated with a burr. The patient was symptomfree with no recurrence of the disease. We postulate that the device used in arthroscopic excision affects the surgical outcome and hence, due consideration should be given before surgery. However, complete excision of a large lesion may be difficult using an arthroscope and in some cases, open excision would be a better treatment option. Weber and Morrey [4] reported only two out of fourteen patients had a capsular release. Generally, removal of the nidus without capsular release allows resolution of the inflammation and return of nearly normal range of elbow motion. Kamrani et al. [10] also reported the flexion contracture resolves spontaneously after removal of the nidus, and there is no obligation to do a capsular release in all patients. In this study, with the exception of one in ten patients, functional elbow range of motion was regained. In our study, although we had observed preoperative limited elbow range of motion, capsular release was not performed. The patient regained full range of motion at 3 months after surgery.

In conclusion, intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the elbow has pathologic features of typical osteoid osteoma with different clinical features. We report a case of delayed diagnosis of an intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the elbow successfully treated arthroscopically. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma must be taken into account in patients with unexplained monoarthritis to avoid catastrophic results to the joint.

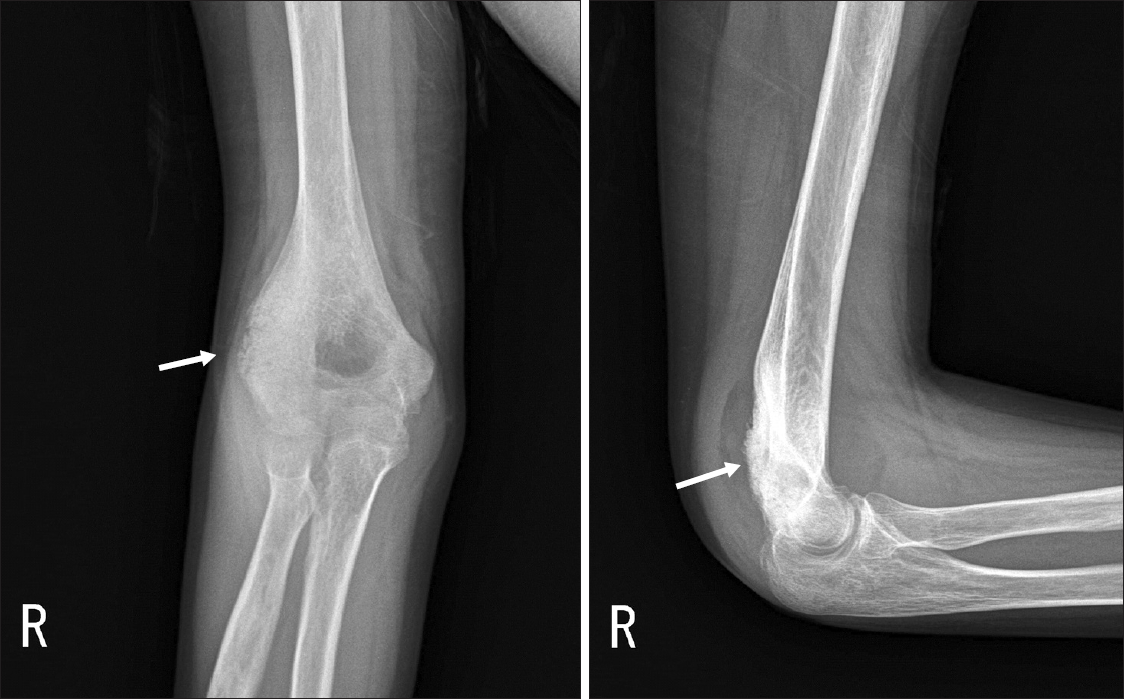

Fig.┬Ā1.

Plain radiographs show periarticular osteopenia and periosteal reaction in the distal humeral metaphysis.

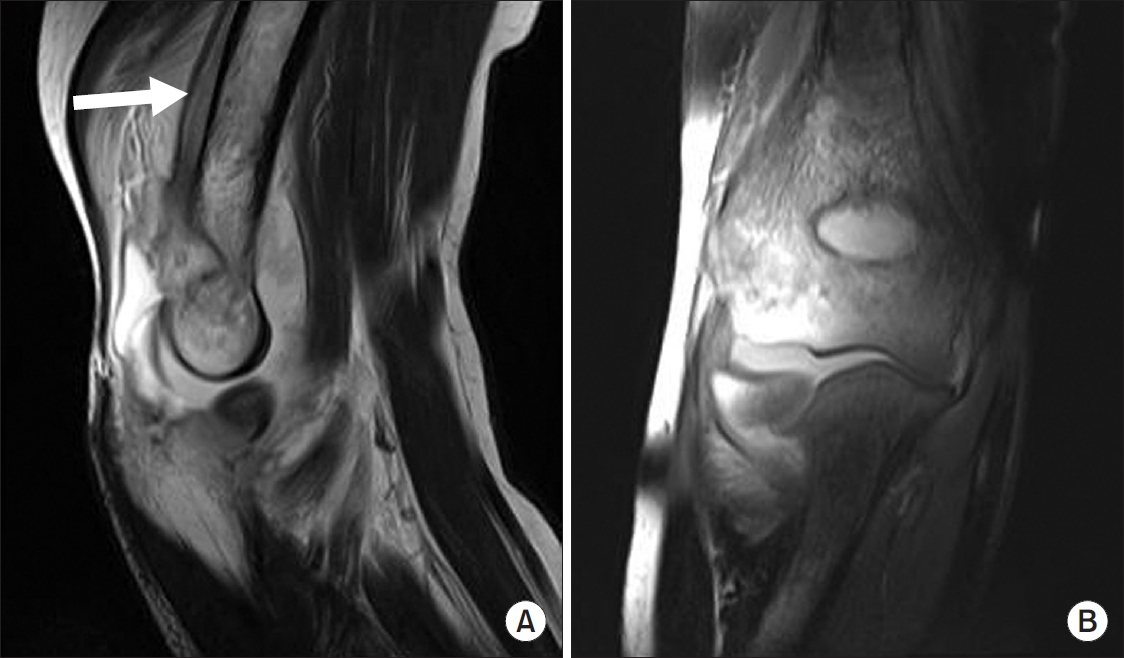

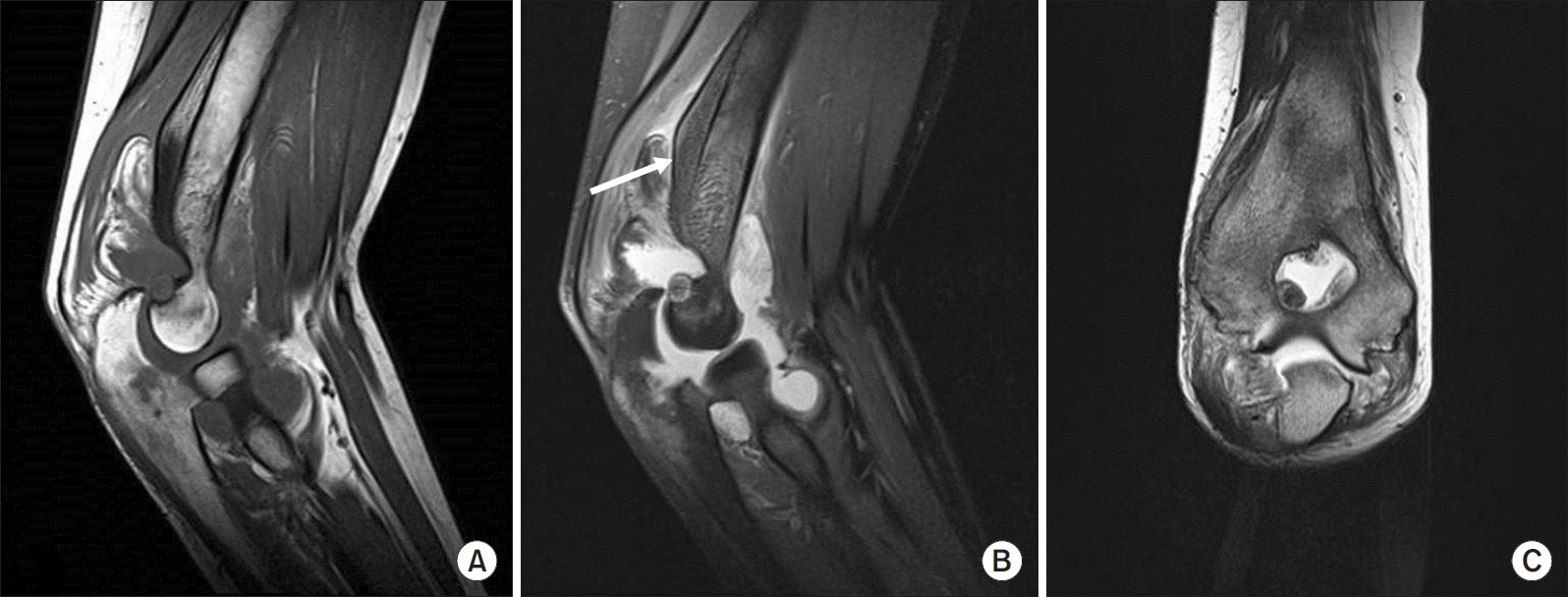

Fig.┬Ā2.

(A) Diffuse periosteal reaction was seen on the sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (white arrow). (B) T2-weighted coronal image showed increased signal intensity of surrounding soft tissue and bone marrow at the distal humerus lateral condyle.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Increased extensive periosteal reaction with dystrophic calcification is observed in plain radiographs as compared to 12 months ago (white arrows).

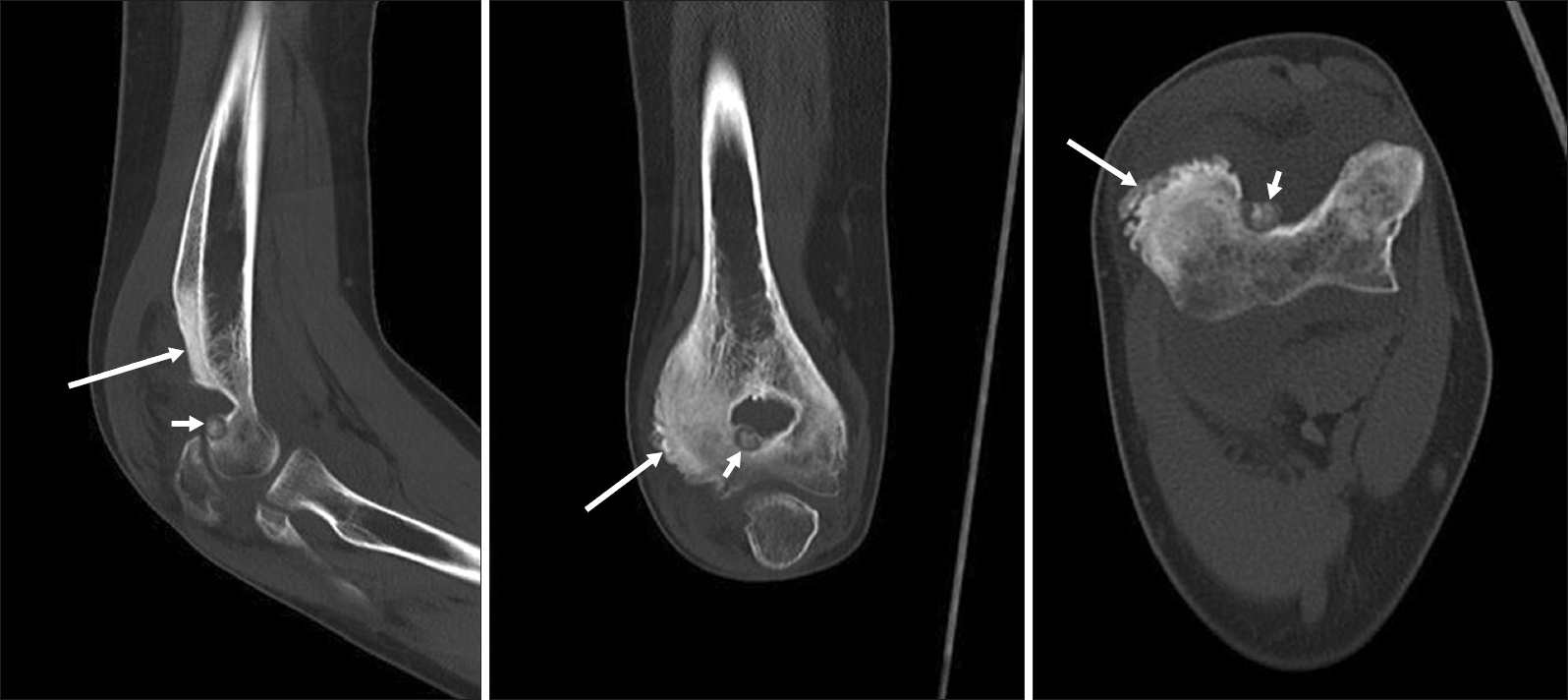

Fig.┬Ā4.

A 5├Ś3├Ś3-mm-sized calcified nidus is clearly seen in computed tomography images (short arrows). Diffuse periosteal reaction is observed above the olecranon fossa on the sagittal image (long arrow). Lateral condyle sclerosis was observed on the axial and coronal image (long arrows).

Fig.┬Ā5.

(A) Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows marked hypertrophic synovitis with joint effusion and a 6├Ś3.5├Ś3-mm-sized intermediate-low signal intensity nodular lesion in the olecranon fossa. (B) T2-weighted image showed a nodular lesion with central intermediate-low signal intensity surrounded by intermediate signal intensity. Periosteal reaction is more extensive in the distal humeral metaphysis than seen 12 months ago (white arrow). (C) Bone marrow edema was slightly subsided on the MRI as compared to 12 months ago.

Fig.┬Ā6.

Bone scan shows increased uptake of tracer on right elbow compared to left one.

RT: right, ANT: anterior.

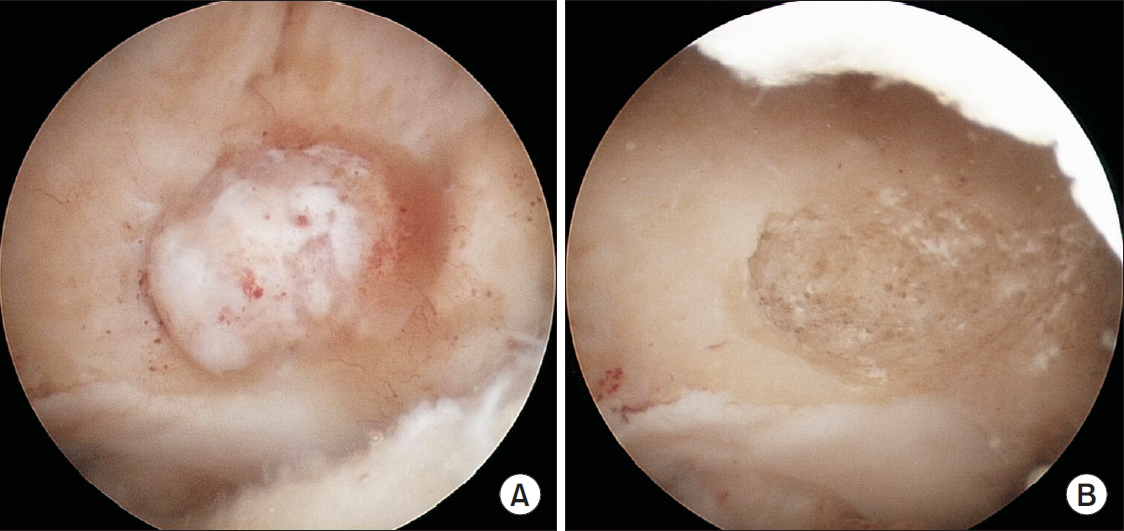

Fig.┬Ā7.

(A) A soft reddish fragment was excised with a grasper and curette under arthroscopic visual control. (B) Complete excision of the lesion.

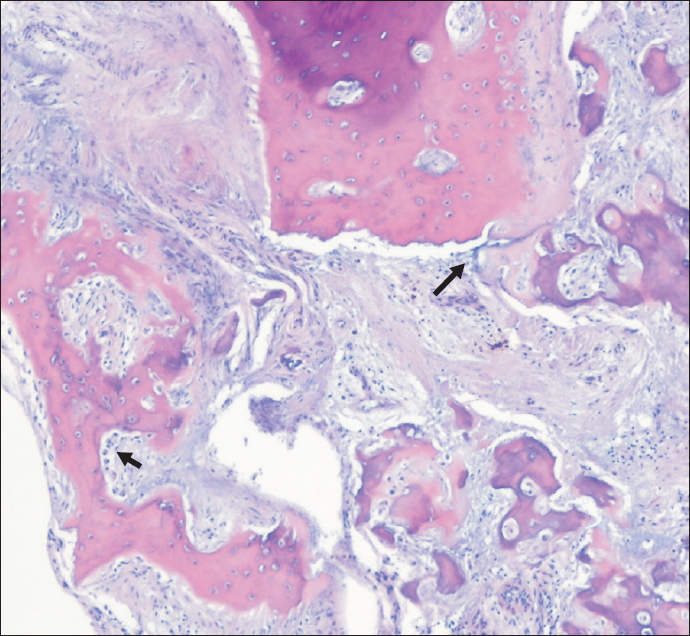

Fig.┬Ā8.

The irregular bone trabeculae in cellular and vascular stroma with osteoblastic rimming (black arrows) illustrates typical features of osteoid osteoma (H&E, ├Ś40).

References

1. Szendroi M, K├Čllo K, Antal I, Lakatos J, Szoke G. Intraarticular osteoid osteoma: clinical features, imaging results, and comparison with extraarticular localization. J Rheumatol 2004;31(5):957ŌĆō64.

2. Cotta AC, de Melo RT, de Castro RCR, et al. Diagnostic difficulties in osteoid osteoma of the elbow: clinical, radiological and histopathological study. Radiol Bras 2012;45(1):13ŌĆō9.

3. Franceschi F, Marinozzi A, Papalia R, Longo UG, Gualdi G, Denaro E. Intra- and juxta-articular osteoid osteoma: a diagnostic challenge: misdiagnosis and successful treatment: a report of four cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006;126(10):660ŌĆō7.

4. Weber KL, Morrey BF. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: a diagnostic challenge. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999;81(8):1111ŌĆō9.

5. Font Segura J, Barrera-Ochoa S, Gargallo-Margarit A, CorreaV├Īzquez E, Isart-Torruella A, Mir Bullo X. Osteoid osteoma of the distal humerus mimicking sequela of pediatric supracondylar fracture: arthroscopic resection-case report and a literature review. Case Rep Med 2013;doi: 10.1155/2013/247328.

6. Contreras A, Isasi C, Silveira J, Barbadillo C, Mulero J, Andreu JL. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma at the elbow: report of a case and review of the literature. J Clin Rheumatol 2000;6(4):218ŌĆō20.

7. Corbett JM, Wilde AH, McCormack LJ, Evarts CM. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma; a diagnostic problem. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1974;(98):225ŌĆō30.

8. Sherman MS. Osteoid osteoma associated with changes in adjacent joint; report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1947;29(2):483ŌĆō90.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 22,848 View

- 33 Download

- Related articles in Clin Should Elbow

-

Arthroscopic Excision of Heterotopic Ossification in the Supraspinatus Muscle2020 March;23(1)