Current Trends for Treating Lateral Epicondylitis

Article information

Abstract

Lateral epicondylitis, also known as ‘tennis elbow’, is a degenerative rather than inflammatory tendinopathy, causing chronic recalcitrant pain in elbow joints. Although most patients with lateral epicondylitis resolve spontaneously or with standard conservative management, few refractory lateral epicondylitis are candidates for alternative non-operative and operative modalities. Other than standard conservative treatments including rest, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, orthosis and physical therapies, nonoperative treatments encompass interventional therapies include different types of injections, such as corticosteroid, lidocaine, autologous blood, platelet-rich plasma, and botulinum toxin, which are available for both short-term and long-term outcomes in pain resolution and functional improvement. In addition, newly emerging biologic enhancement products such as bone marrow aspirate concentrate and autologous tenocyte injectates are also under clinical use and investigations. Despite all non-operative therapeutic trials, persistent debilitating pain in patients with lateral epicondylitis for more than 6 months are candidates for surgical treatment, which include open, percutaneous, and arthroscopic approaches. This review addresses the current updates on emerging non-operative injection therapies as well as arthroscopic intervention in lateral epicondylitis.

Introduction

Lateral epicondylitis, commonly known as ‘tennis elbow’, is an orthopedic condition affecting 1% to 3% of the general population, mostly over 40 years of age and with equal gender distribution [1,2]. Most previous reports indicate that within 1 year of treatment, 70% to 90% lateral epicondylitis shows a clinical course of spontaneous resolution or a response to conservative management, including rest, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, orthosis, physical therapies, and injection [3]. Especially, numerous recent studies have proved that injections with corticosteroid, platelet-rich plasma, autologous blood products, or botulinum toxin have presented satisfactory effects on pain relief and functional improvement in patients with lateral epicondylitis who are refractory to pain medications, but do not prefer surgical remedies [4].

Since lateral epicondylitis results from excessive stress, repeated microtrauma, and degenerative changes on the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) tendon, both arthroscopic and open surgery are often considered in poor potentials for conservative management [5]. Indications for surgical treatment remain controversial and lacks a well-established consensus, but surgical intervention, especially arthroscopic approaches, is often advantageous in patients with persistent disabling pain even after 6 months of nonoperative treatment [6]. Arthroscopic approaches are more beneficial for the visual inspection of intraarticular structures, a short rehabilitative period, and less postoperative morbidity [7].

All previous studies addressing nonoperative and operative treatments of lateral epicondylitis were identified by thoroughly reviewing the medical databases, PubMed and Scopus. Studies were selected after further categorization as injection therapy, arthroscopic surgery and lateral epicondylitis, and only studies with a level of evidence higher than 4 were included for the current review. We selected previously published studies by narrowing our searches in the published years between 2014 and 2019. Studies with (1) non-English manuscripts, (2) case series, and (3) studies with a short follow-up period less than 6 months, were excluded.

The purpose of our present study is to introduce current updates on the available injections and arthroscopic surgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis by reviewing the most recent articles, in order to draw a more comprehensive conclusion on advantages of both interventional therapy with injection and arthroscopic approaches.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of lateral epicondylitis has no consensus, but the most common anatomic site of origin is known to be the ECRB, even though the annular ligament, lateral capsule, radial nerve, and extensor digitorum communis are associated as causative factors in lateral epicondylitis [8]. Degenerative tendinopathy is usually the outcome of microtrauma at the origin of the extensor tendon due to repetitive wrist extension and alternating forearm rotation by excessive use and stress. Tendon injuries in lateral epicondylitis share common histologic findings, characterized by ‘angiofibroblastic hyperplasia’, showing a disorganized mix of immature collagen fibers with fibroblastic and vascular components [9]. In addition, various microscopic studies on tissues of lateral epicondylitis have revealed that histologic features were a consequence of failure in reparative responses in ECRB, rather than a result of an inflammatory process [10].

Clinical Presentation

The most frequent complaint described by patients with lateral epicondylitis is pain at the lateral aspect of elbow, often associated with radiating pain down the forearm [3]. The pain is characteristically sharp and aggravated during wrist extension or forearm supination and pronation. Patients usually experience an insidious onset of pain at the anterior border of the lateral epicondyle, which may gradually develop into weakness; however, the symptoms in lateral epicondylitis vary from an occasional ache over the bony prominence of lateral epicondyle to recalcitrant debilitating sharp pain. A physical examination of patients with lateral epicondylitis, along with the patient history, needs to be comprehensive to rule out other possible diagnoses involving cervical spine, shoulder joint, and inflammatory joint diseases, which may mimic symptoms of lateral epicondylitis [4].

Diagnosis

Even though lateral epicondylitis is mostly diagnosed clinically, patients with pain over the lateral epicondyle are first evaluated with plain radiographs. Simple radiographs often reveal calcification in the surrounding tissues or insertion sites of the extensor tendons, and are beneficial in exclusion of other joint or bony pathologies. In addition, advances in radiologic techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography (US), are useful in evaluating the disease severity, presence of osteochondral defects, degree of ligamentous injury or tear, and differential diagnosis [11]. MRI is also advantageous in the detection and evaluation of extra- and intra-articular architecture and pathologies, such as presence of joint effusion, muscle edema, synovitis, cartilaginous defects, and other ligamentous abnormalities. In addition, the US findings of lateral epicondylitis characteristically reveal structural changes of the affected region, such as thickening and heterogenous echotexture of the common extensor tendon as well as increased blood flow under doppler [12].

Treatment Options

Lateral epicondylitis can largely be treated with conservative and nonoperative measures, and spontaneous resolution is generally expected within 8 to 12 months [7]. Since long-term application of a wrist brace or splinting may cause negative consequences, including forearm muscle weakness and atrophy, a combination of conservative management methods before development of chronic pain and functional disability is expected to yield superior clinical outcomes in pain resolution, wrist range of motion, and grip strength [13].

Nonoperative measures such as intra-articular injections with corticosteroid, platelet-rich plasma, botulinum toxin or lidocaine, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy, have also been extensively evaluated in recent years. Among the numerous injection modalities available, corticosteroid injection remains the mainstream of intra-articular treatment in lateral epicondylitis, and its effect can be augmented in a mix with lidocaine injection [3]. A recent study on botulinum toxin on ECRB under electromyographic (EMG) guidance revealed analgesic effect due to inhibited pain neurotransmission, and improved healing outcomes in tendon injury by a decrease in tension at the site of enthesis and an increase in muscular blood flow [14]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that autologous blood products (such as autologous blood and platelet-rich plasma) have an intermediate-term effect on pain relief and elbow function, as compared to corticosteroid injection that exerts a short term effect [15]. In addition, efficacy of extracorporeal shock wave therapy has proven effective in pain relief and elbow function improvements, including muscle function and elbow range of motion [16].

Although majority of lateral epicondylitis cases can be managed conservatively or non-operatively, approximately 4% to 11% patients require surgical interventions that include open, percutaneous, or arthroscopic approaches, due to chronic recalcitrant elbow pain and functional disability [3]. Surgical treatment includes ECRB tendon release, and resecting the tendinosis portion of the affected tendon via various approaches available, as per the surgeon’s discretion. However, careful consideration is advised in selecting patients for surgical indications, such as symptom duration longer than 6 months, or persistent severe pain despite conservative management described above [17]. Patients who have undergone previous elbow surgical management such ulnar nerve transposition, are better opted for open surgical approaches since the possibility of neurovascular injury is relatively higher in arthroscopic approaches in the elbow than in other joints [18]. Furthermore, to return to normal daily life and tolerate pain in patients receiving surgical treatments, postoperative rehabilitation is essential to achieve normal range of motion in the elbow joint, with active physical therapy involving eccentric strengthening exercises.

Current Updates on Interventional Therapy with Injection

Non-invasive interventional therapy with injections is widely used in orthopedic patients with painful joint disability, with satisfactory outcomes. The technique has been extensively studied using various injectates such as corticosteroids, analgesics, newer biologic therapies, and even stem cell therapies. Before considering surgical intervention in lateral epicondylitis, an injectable interventional therapy is expected to have less invasive and more satisfactory clinical outcomes for symptom resolution as well as functional improvement.

Corticosteroid is a frequently used injection in orthopedics, and is the mainstay treatment modality for lateral epicondylitis. However, its anti-inflammatory properties are reported to have only short-term to intermediate-term efficacy for pain relief and improved clinical scores [19]. Hence, the repetitive use of corticosteroids in lateral epicondylitis is discouraged due to adverse effects after long-term use of steroid injections (e.g., weakening of tendon), minimal long-term pain controlling outcome, and the nature of lateral epicondylitis being due to microtrauma rather than inflammatory process [20].

Botulinum toxin, a well-known neurotoxin that blocks neural impulses by inhibiting acetylcholine and consequent paralysis of targeted muscle, is also a widely studied injectate. The use of botulinum toxin induces spontaneous repair of the affected extensor tendon during a temporary period of rest and paralysis of the extensor muscle, and decreases pain perception by releasing cellular mediators such as substance P, glutamate, and bradykinin [21]. Several previous studies have demonstrated favorable long-term clinical outcomes in pain and clinical scores after administering botulinum toxin in refractory chronic lateral epicondylitis, as compared to analgesics, physiotherapy, electrotherapy, and peritendinous injection treatment; botulinum may therefore be an alternative treatment modality in potential patients for surgical intervention [12,22]. Moreover, hyaluronic acid, one of the main components in synovial fluid cartilages and tendon extracellular matrix, is naturally produced in the tendon sheath, and has proven to yield beneficial effects in pain relief and functional improvement after articular administration in osteoarthritis and soft tissue injuries [23]. A study on periarticular injection of hyaluronic acid in sports athletes with lateral epicondylitis has shown superior pain relief and maximal grip strength compared to the control, along with an earlier return to normal sport activities [24].

Furthermore, autologous blood products have gained popularity in the treatment of tissue healing in orthopedic settings. Platelet-rich plasma and autologous whole blood are proven to have tendon regenerative effects by supplementing with various growth factors such as platelet derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, platelet factor 4, interleukin-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor, and by increasing vascularity to eventually increase tendon thickness and improve the anatomical tendinous morphology [25]. Since corticosteroids, considered the mainstay of an intervention therapy with injection, have limited long-term effects and results in tendon degeneration with chronic use, biologic enhancement injectates like platelet-rich plasma or autologous blood are expected to exert their efficacies and long term effects in pain resolution as well as tendon regeneration [26]. A previous meta-analysis has proved that injection therapy with autologous blood shows superior outcomes not only in reduction of pain associated with lateral epicondylitis to corticosteroid injection, but also in functional improvement [27].

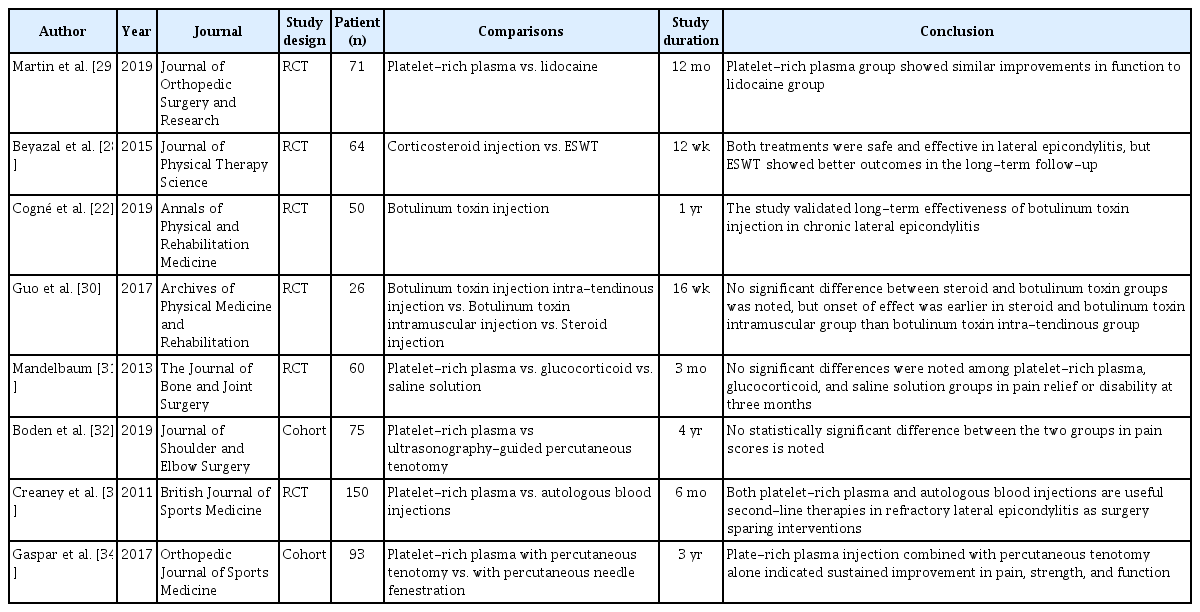

Other biological enhancement injectates, such as bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) and autologous tenocyte injectate (ATI), have gained the attention of patients who are reluctant to undergo surgical intervention for lateral epicondylitis. BMAC is the emerging treatment for bone and cartilaginous injuries by restoration of natural microstructures and supplementation of mesenchymal and hematopoietic stem cells, platelets, growth factors, cytokines, and immunomodulatory cells. Previous studies have indicated beneficial effects of BMAC on osteochondral and chondral defects, but the long-term effects are still under investigation [26]. Direct injection of autologous tenocyte (derived from the skin, adipose tissue, and tendon stem/progenitor cells) is another option for non-operative therapeutic modalities to regenerate the tendon having characteristics of poor cellularity, low vascularity and low potential for tendinous regeneration [26]. Such disadvantageous properties hamper the healing process of the tendon, resulting in not only poor tendon regeneration but also development of large scar tissue around the injury site, thereby making it more vulnerable to additional injuries. The ATI is prepared and injected under US guidance for better transfer at the site of tear or hypoechogenic tendinous region showing discontinuity. A study on the long-term efficacy of ATI treatment with a follow-up period of more than 4 years, reports symptomatic and functional improvement without adverse effects, complications, or infections in >70% participants. However, ATI treatment is still being explored with animal studies and preclinical trials, and requires further researches with a larger study population to determine the efficacy and safety (Table 1) [22,26,28-34].

Current Updates on Arthroscopic Surgery

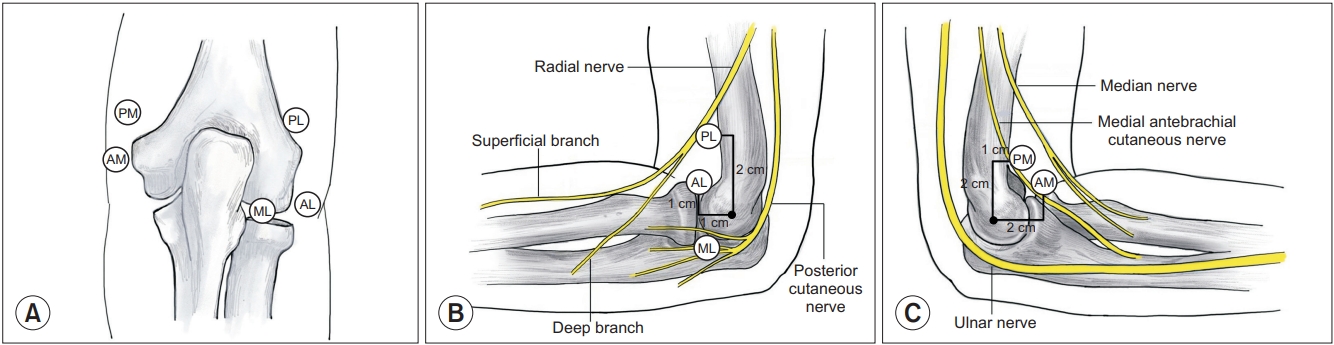

Since the initial report on arthroscopic debridement in recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis by Baker et al. [28], there have been other reports on satisfactory outcomes of arthroscopic treatment in the clinical performance and daily functions of patients. In elbow arthroscopy, the patient is positioned in either the lateral decubitus or prone position, usually using two portals. A proximal anteromedial portal is established as the viewing portal, inserted at 2 cm proximal to medial epicondyle and 1 cm anterior to the medial intermuscular septum for better visualization and protection of the radial nerve; in addition, a proximal anterolateral portal is placed at 2 mm directly anterior to tip of the lateral tip of lateral epicondyle at the level of proximal margin of the capitellum, and functions as the key surgical portal (Fig. 1) [16]. Even though these two portal sites are most popularly used in elbow arthroscopy for lateral epicondylitis, other portals, such as accessory anterior, direct lateral, distal ulnar, direct posterior, and posterolateral portals, can also be used, after considering the sites of joint pathologies.

Portals around the elbow for arthroscopy. (A) Posterior aspect, (B) lateral aspect, and (C) medial aspect. PL: proximal lateral portal, AL: anterior lateral portal, ML: mid-lateral portal, PM: proximal medial portal, AM: anterior medial portal.

Once the two portals are inserted, the lateral capsule of elbow joint is released after debridement of lateral synovitis. Origin of ECRB tendon is released from the anterior aspect of lateral epicondyle, and resected until the visualization of normal tendon tissue, with or without decortication of the lateral, non-articular surface of lateral epicondyle. During the release of ECRB, it is important not to resect the extensor aponeurosis, which is located behind ECRB and is posterior to the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), lateral ulnar collateral ligament, and surrounding neurovascular structures [17].

Arthroscopic approaches in lateral epicondylitis, along with percutaneous and open approaches, indicate satisfactory surgical outcomes for pain, function, return to normal activities, and postoperative grip strength; however, arthroscopic treatment is more advantageous than the other two approaches due to better visualization of the entire intra-articular structures [1,2]. A recent systemic review of the three surgical techniques has revealed that postoperative complications, such as total or partial nerve injury and elbow joint instability among the three techniques, indicates equivalent outcomes, although another previous study reported lower complication rates with the arthroscopic approach as compared to the other two techniques, despite a high learning curve [8].

In addition, various randomized controlled trial studies have recently examined the relationship between arthroscopic treatment and other operative and non-operative therapeutic approaches. Clark et al. [6] utilized various scoring systems such as disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH), visual analogue scale (VAS) pain, and patient-rated tennis elbow evaluation (PRTEE) score, in order to prospectively evaluate post-surgical outcomes of patients who had received either arthroscopic or open releases of the common extensor tendon. No significant differences were detected between the two approaches in any of the scoring systems; nonetheless, both groups showed improvement from the preoperative to postoperative assessment in both pain and function; the study results are consistent with the previous comparative analysis between open and arthroscopic treatment. In addition, Merolla et al. [35] compared efficacy of arthroscopic ECRB release and autologous platelet-rich plasma injection through a randomized controlled trial in chronic recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis patients. They confirmed that platelet-rich plasma injections were most effective in short and intermediate term improvement in pain and function, whereas arthroscopic treatment is minimally invasive and is more effective in long term improvement; therefore, the study provides a better understanding in applications of various treatment modalities according to preference and expectation of the patient.

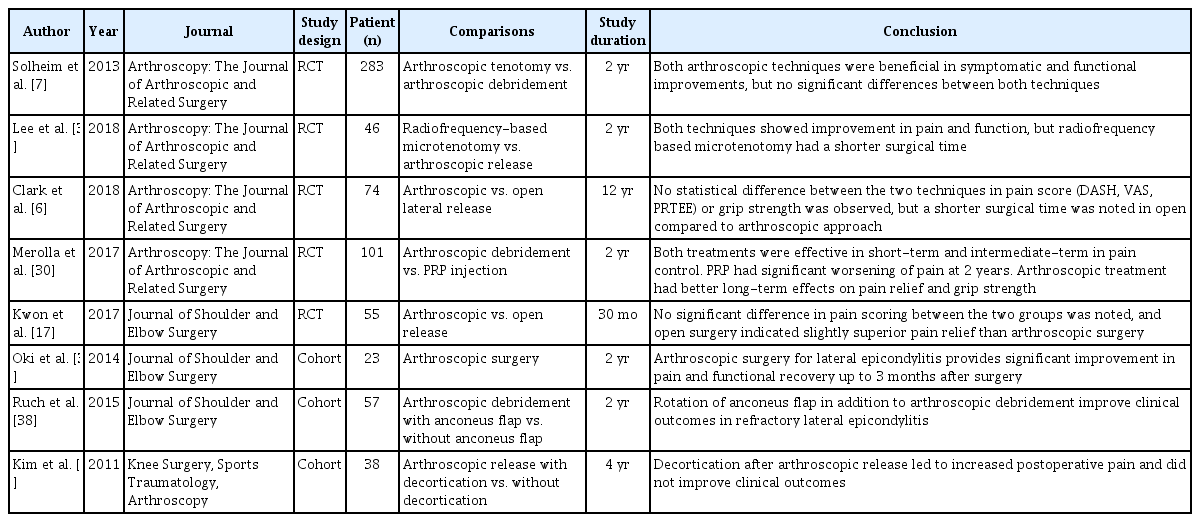

Even though it has been reported that all patients with arthroscopic treatment of lateral epicondylitis were satisfied with postoperative clinical outcomes in pain improvement and functional gain, contraindications for arthroscopic treatment in lateral epicondylitis have not been adequately addressed. However, prior operative management in elbow joints or arthritic changes involving the whole elbow joint, are considered relative contraindications to arthroscopic treatment in lateral epicondylitis, and are expected to be better addressed with open approaches (Table 2) [6,7,17,18,35-39].

Conclusion

In patients with refractory chronic lateral epicondylitis, various treatment options are available, depending on the expectation and willingness of the patient. Recalcitrant debilitating pain lasting for more than 6 months despite receiving standard conservative treatment is indicative for surgical treatment. However, injectates such as corticosteroid, lidocaine, autologous blood, platelet-rich plasma, and botulinum toxin, in addition to the newly emerging biologic enhancement injectates like BMAC and ATI, are available to relieve pain and improve functional outcomes. Furthermore, in cases of failed attempts with the available nonoperative treatments, arthroscopic tendon release is a minimally invasive technique with promising long-term optimal clinical and functional outcomes in patients with chronic lateral epicondylitis

Notes

Research Ethics

Review article does not need an IRB approval.

Conflict of interest

None.

Financial support

None.