Management of Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries in Overhead Athletes

Article information

Abstract

Ulnar collateral ligament injuries of the elbow are frequent among overhead athletes. The incidence of ulnar collateral ligament reconstructions (UCLRs) in high-level players has increased dramatically over the past decade, but the optimal technique of UCLR is controversial. Surgeons need to manage the patients’ expectations appropriately when considering the mode of treatment. This article reviews current studies on the management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries, particularly in overhead athletes.

Introduction

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is a crucial structure to an overhead athlete, particularly baseball pitchers. The number of UCL injuries in pitchers has increased over the last decade [1,2]. The reasons why some pitchers have UCL tears and others do not are unclear, but some studies have reported many risk factors, which include pitching more than 100 innings per year, pitching for multiple teams, pitching while fatigued, pitching with higher velocity, pitching on consecutive days, pitching while growing up in warmer climates, and pitching with a glenohumeral internal deficit (GIRD) or a loss of total arc of shoulder motion [3-7]. The management of players who sustain a tear of their UCL presents a variety of problems for both the player and treating surgeon.

Clinical Evaluation

Patients with a UCL injury usually complain of vague elbow pain with a change in their throwing speed and accuracy [8]. Pitchers sometimes present with an acute traumatic event, in which they feel a “pop” in their elbow after a certain pitch without having suffering pain before the injury. When a throwing athlete presents with medial elbow pain, it is important to take a thorough history, including the exact location of the pain, onset of symptoms, and phase of the pitching cycle when the symptoms arise [9]. Ulnar nerve symptoms, whether they are present at rest or during motion (pitching), such as numbness and paresthesia of the 4th and 5th fingers, should be noted.

Palpation should be done with a consideration of the tenderness over the medial epicondyle, sublime tubercle, and olecranon. The range of motion (ROM) of both elbows should be checked, and attention should be paid to any extension loss or pain with terminal extension that could indicate posteromedial impingement [10]. The shoulder ROM should be checked with an assessment of scapular dyskinesis, GIRD, and a loss of total shoulder rotation of the throwing arm because these findings have been correlated with a higher risk of elbow injuries [4].

Special tests to evaluate the UCL have been performed, including the valgus stress test, moving valgus stress test, and milking maneuver. The milking maneuver is performed with the forearm supinated fully, and the elbow flexed beyond 90 degrees. The thumb is then pulled laterally, producing a valgus force on the elbow. Pain, instability, or apprehension is a positive test that is indicative of an injury to the UCL (Fig. 1). The moving valgus is positive if the patient complains of pain during a valgus load of the elbow while also flexing and extending the elbow between 70 and 120 degrees of flexion. Studies have found a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 75%, respectively, in diagnosing tears of the UCL [11].

Imaging

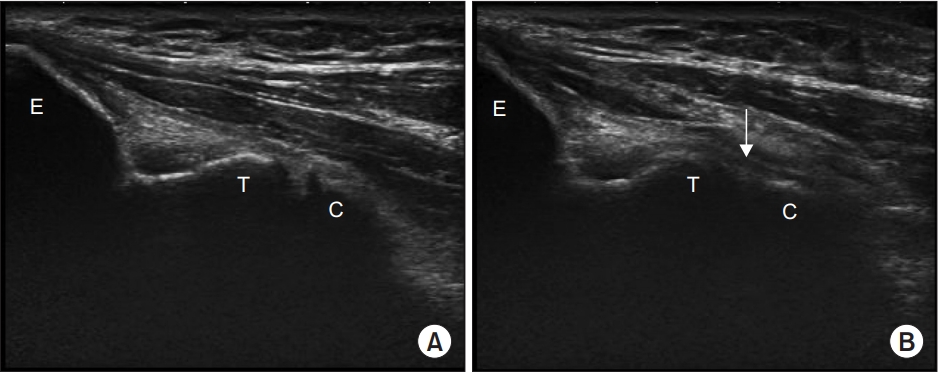

Plain radiographs of the elbow should be evaluated for the posteromedial osteophytes, calcification, degenerative changes to the ulnohumeral and radiocapitellar joints, capitellar osteochondral defects, loose bodies, open physis, or stress fractures. Stress X-rays to identify medial widening may be performed, and a 1 to 3 mm difference between elbows can indicate a UCL injury. Stress ultrasound may also be a valuable tool to assess the medial gapping and integrity of the ligament (Fig. 2) [12,13].

Ultrasound images of a patient with ulnar collateral ligament insufficiency at rest (A) and with valgus stress applied showing ulnahumeral joint gapping (arrow) (B). E: epicondyle, C: coronoid process, T: trochlea.

Although X-rays and ultrasound may provide useful information, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is the gold standard imaging modality to evaluate both full and partial thickness UCL tears (Fig. 3) [14]. The intact UCL has low signal on the T1-weighted images, whereas a tear will be bright on the T2-weighted images because of edema within the ligament. MRA with intraarticular gadolinium contrast improves the diagnosis rate of partial undersurface tears. MRI can also identify concomitant edema and injury in the flexorpronator origin and posteromedial ulnohumeral chondromalacia [15]. A computed tomography (CT) study is often unnecessary in a primary UCL tear but may be needed when there are concerns for posteromedial osteophytes, stress fracture, and enthesophytes on the sublime tubercle. In addition, in patients with a previous ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction (UCLR), a CT scan can be useful for evaluating the placement of the ulnar and humeral tunnels and used as a guide during revision surgery [16].

Treatment

Non-surgical Treatment

Non-surgical treatment for the UCL consists of a rest from aggravating activities, such as throwing, rehabilitation, and a progressive return to a throwing program. The treatment course requires several months, and the process must focus on maximizing the shoulder ROM, increasing the core strength, posterior capsule stretching, and proper scapulothoracic motion. Nonsurgical treatment of UCL injuries with rest and rehabilitation has shown success rates of less than 50% for pitchers returning to their sports at previous levels [17]. Ford et al. [18] reported that there was a subset of patients in professional baseball players with incomplete UCL tears diagnosed by MRI, who had a >80% return to sports rate after non-surgical treatment. The modalities used were electric stimulation, soft tissue mobilization, massage, scraping, ultrasound, and laser therapy.

Although the function and integrity of the UCL are critical to throwing sports, racquet sports, hockey, and gymnastics, a normal or near normal UCL is usually unnecessary for patients who do not engage in these sports [19]. Daily activities and other sports, such as soccer, do not require a competent UCL, so most patients do not require surgery [20].

Newer biological treatment modalities, such as platelet rich plasma (PRP) and pluripotent mesenchymal cells (stem cells), have been used with encouraging results. Recent studies have reported that more than 70% of players with UCL tears return to sports after a PRP injection with rehabilitation [21].

Certain tear patterns that have a poor prognosis with nonsurgical management, such as high-grade partial tears, complete tears, and avulsions of the distal ligament attachment on the ulna, may benefit from early surgical intervention [22].

Surgical Treatment

The indications for surgery are patients with an accurate diagnosis of a UCL injury who require a return to throwing sports, have failed conservative treatment, and are willing to participate in post-surgery rehabilitation. In competitive athletes, seasonal timing may influence the decision for surgical intervention.

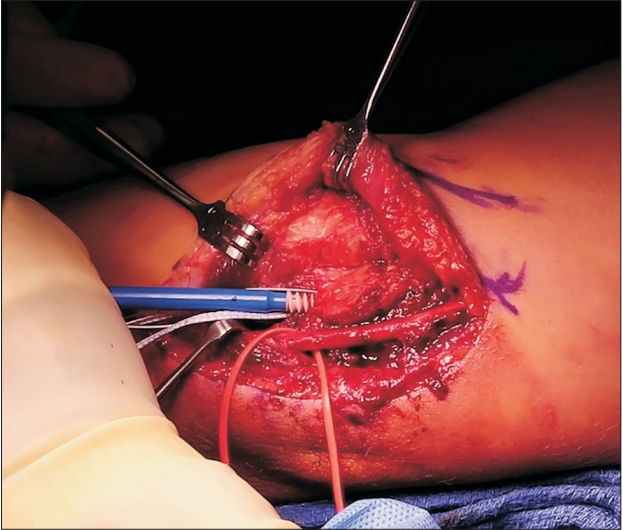

Surgical treatment can be divided into UCL repair or UCLR. Although the results after UCL repair are believed to be inferior to UCLR, recent studies have shown otherwise, with some reporting that more than 90% of patients return to sports after repair [23,24]. Recently, a modification of the repair was introduced, in which the repair was augmented with a synthetic tape fixed with bone anchors at both ends (InternalBrace®; Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) to prevent excessive stress on the repaired UCL and might permanently reinforce the healed ligament (Fig. 4) [25,26].

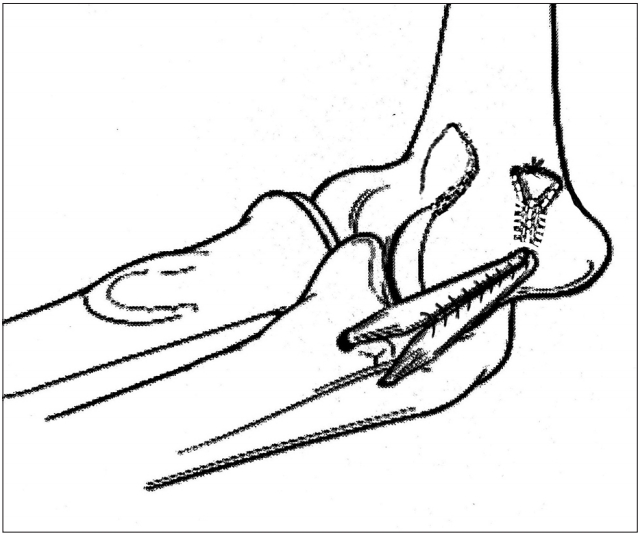

In 1986, after Jobe et al. [27] first described the UCLR technique, which is famously known as ‘Tommy John surgery’, the procedure has undergone multiple modifications regarding the approach, graft choice, and methods of graft fixation to reduce the complications and improve the outcomes [20]. The earlier figure eight configuration had some drawbacks, such as difficulty of maintaining tension because of the large number of bone tunnels in the medial epicondyle [28]. Several modifications of the initial Dr. Jobe’s procedure, such as the popular docking technique, have been made (Fig. 5) [29]. The results of several other techniques are encouraging. Dines et al. [15] reported 22 patients who underwent UCLR using the DANE-TJ technique and found that 19 of the 22 patients had excellent results. Cain et al. [30] reported 743 patients, who underwent UCLR with American Sports Medicine Institute modification of the Jobe technique, and found that 83% returned to their previous level of activity. The initial UCLR technique described the release and repair of the flexor-pronator mass. Modifications of the technique have evolved to muscle splitting of the flexor carpi ulnaris to decrease the rate of postoperative ulnar neuropathy [31].

Docking ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction, with the graft docked into the medical epicondyle and tied over a bone bridge.

Several graft choices for UCLR, including ipsilateral or contralateral palmaris longus autograft, hamstring autograft, hamstring allograft, and others, are available [20]. No studies have found one graft to be biomechanically and clinically superior [32,33]. In addition, no single surgical technique or method of fixation has been proven to be superior.

Postsurgical Rehabilitation

The length of rehabilitation after surgery is greater than the length after conservative treatment. The current consensus is to avoid accelerated rehabilitation, which may be a risk factor with a reconstructed UCL [34]. The rehabilitation process is typically divided into four phases [35]. Rehabilitation phase 1 (postoperative weeks zero to three) consists of prevention of stiffness, promotion of healing and simultaneous protection of the reconstructed graft with a hinged elbow brace. The goals of phase 2 (weeks four to eight) are to gain strength and gain a full ROM. During phase 3 (weeks nine to 13), the rehabilitation is focused on flexibility and neuromuscular control. Progression towards sports related activities, utilizing plyometrics, is made during this phase. The progression of a throwing program is made during phase 4 (weeks 14 to 26). Full competition throwing is usually permitted at seven to nine months, and the pitchers are ready to return to a game at approximately 10 to 18 months.

Results

Despite the common perception that pitchers increase their velocity after UCLR, although pitchers often do regain their preinjury speed or lose a small amount of velocity, they do not exceed their average preinjury velocity [36,37]. Although most studies report >80% return to sports after UCLR, several confounding factors can adversely affect the outcome. A concomitant tear of the flexor pronator mass, associated ulnohumeral arthrosis, and calcification of the native UCL can decrease the success of UCLR, and the surgeons should manage patient expectations accordingly when any of these confounding factors are present [38-40].

As the number of UCLR performed increases, the number of revision UCLR procedures will also increase. Revision UCLR surgery is a concern because the results are poorer than primary UCLR. Studies have shown that the revision rate for UCLR is between 3.9% to 15% [1,41]. Even in the hands of expert surgeons, the rate of those returning to sports after revision UCLR is reported to be 65.5% [42].

Summary

Pitchers with a decrease in velocity and loss of accuracy in the setting of medial elbow pain should be assessed thoroughly for a UCL insufficiency. Although MRI or MRA are the imaging modalities of choice, new dynamic ultrasound imaging provides a rapid evaluation on the field and during postoperative rehabilitation. No single outperforming UCLR technique or graft is available. Therefore, the patient’s expectations need to be considered when discussing the treatment options. When performing UCLR, surgeons should choose a surgical technique that minimizes iatrogenic injury to the flexor-pronator group and ulnar nerve, preserves the native UCL, and incorporates the graft into the UCL with adequate fixation to the anatomic footprint region of the humerus and ulna.

Notes

Research Ethics

Review article does not need an IRB approval.

Conflict of interest

None.

Financial support

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jung-Gon Kim (Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital) who provided the illustrations for this article.