Peri-anchor cyst formation after arthroscopic bankart repair: comparison between biocomposite suture anchor and all-suture anchor

Article information

Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study is to investigate clinical outcomes and radiological findings of cyst formation in the glenoid around suture anchors after arthroscopic Bankart repair with either biocomposite suture anchor or all-suture anchor in traumatic anterior shoulder instability. We hypothesized that there would be no significant difference in clinical and radiological outcomes between the two suture materials.

Methods

This retrospective study reviewed 162 patients (69 in group A, biocomposite anchor; 93 in group B, all-suture anchor) who underwent arthroscopic Bankart repair of traumatic recurrent anterior shoulder instability with less than 20% glenoid defect on preoperative en-face view three-dimensional computed tomography. Patient assignment was not randomized.

Results

At final follow-up, the mean subjective shoulder value, Rowe score, and University of California, Los Angeles shoulder score improved significantly in both groups. However, there were no significant differences in functional shoulder scores and recurrence rate (6%, 4/69 in group A; 5%, 5/93 in group B) between the two groups. On follow-up magnetic resonance arthrography/computed tomography arthrography, the incidence of peri-anchor cyst formation was 5.7% (4/69) in group A and 3.2% (3/93) in group B, which was not a significant difference.

Conclusions

Considering the low incidence of peri-anchor cyst formation in the glenoid after Bankart repair with one of two anchor systems and the lack of association with recurrence instability, biocomposite and all-suture anchors in Bankart repair yield satisfactory outcomes with no significant difference.

INTRODUCTION

The shoulder is a commonly dislocated joint in the human body. In young patients, recurrence of shoulder instability can occur in up to 90% with some surgical options [1-3]. With the advent and development of suture anchors, arthroscopic Bankart repair has replaced open Bankart repair with a classic transosseous technique. Furthermore, suture anchor has become one of the most important factors for restoration of recurrent shoulder instability [4,5].

The first generation of suture anchors comprised metallic materials (stainless steel or titanium) and could produce stable fixation and satisfactory clinical outcomes. However, many severe complications were reported, such as loosening, intra-articular migration, and protrusion into the shoulder joint resulting in cartilage injury [6-10]. Thereafter, non-metallic second-generation (bioabsorbable and biocomposite) suture anchors were introduced to overcome these complications and are widely used in the arthroscopic field [6,10,11]. Nonetheless, there have been issues related with rapid degradation leading to intraosseous cyst formation and osteolysis [10,12]. Recently, a third generation of suture anchors (all-suture type) was introduced. These all-suture anchors avoid osteolysis due to degradation or cartilage injury caused by a loose body. However, a recent study raised the concern that the all-suture-type anchor created a cyst-like cavity in vivo and resulted in inferior biomechanical properties except ultimate failure load compared to biocomposite suture anchor [13].

The purpose of this study is to investigate clinical outcomes and radiological findings regarding cyst formation in the glenoid around suture anchors after arthroscopic Bankart repair with either biocomposite suture anchor or all-suture anchor in traumatic anterior shoulder instability. We hypothesized that there would be no significant difference in clinical and radiological outcomes between the two suture materials.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (IRB No. 4-2020-0932), with waver of the requirement for patient informed consent.

Study Population

This retrospective study reviewed 211 patients who underwent arthroscopic Bankart repair of traumatic recurrent anterior shoulder instability using either biocomposite suture anchor (SutureTak, Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA; group A) or all-suture anchor (Y-Knot Flex, ConMed Linvatec, Largo, FL, USA; group B) performed by a senior author from January 2011 to February 2017. Patient assignment was not randomized. The indications of surgery were discomfort in activities of daily-living and positive apprehension test.

The inclusion criteria were Bankart lesion with less than 20% glenoid defect on preoperative en-face three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography (CT) and (2) available for a minimum 2-year follow-up after surgery. The exclusion criteria were (1) previous operative history on affected shoulder, (2) revision surgery, (3) unavailability for at least 2 years of follow-up, (4) concomitant rotator cuff repair, (5) combined posterior or multi-directional instability, and (6) lack of follow up magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) or computed tomography arthrography (CTA) after 6 months postoperatively. Finally, 162 patients (69 in group A, biocomposite anchor; 93 in group B, all-suture anchor) who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria and their medical records and radiologic data were reviewed retrospectively.

Functional and Radiologic Assessments

Functional assessments were performed using the following indices: subjective shoulder value (SSV; the percentage value of the affected shoulder compared to that of the normal shoulder), Rowe score, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder score, and shoulder active range of motion (ROM; forward flexion in the scapular plane, external rotation with the elbow at the side and external and internal rotation in 90° of abduction). During each patient visit, an independent examiner evaluated the preoperative and postoperative shoulder functional scores and measured active ROM. We defined recurrence instability as subluxation episode, re-dislocation, or positive apprehension sign at 90° abduction and external rotation of the shoulder. Preoperative radiologic assessments included standing true anteroposterior views of the shoulder in neutral and axillary positions and MRI or MRA studies. Follow-up MRA (3.0-T MR imaging unit, MAGNETOM Tim Trio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) or CTA (SOMATOM Sensation 64; Siemens) was performed 6 months after operation.

Surgical Techniques and Postoperative Rehabilitation

All patients underwent arthroscopic Bankart repair in lateral decubitus position under general anesthesia in the setting of longitudinal traction with 10 lbs. A superior viewing portal, low anterior portal for anchor insertion, and posterior portal for shuttle relay were established. Viewed from the superior portal, a Bankart lesion was identified. After sufficient release of detached anteroinferior labrum, the glenoid edge was prepared. The first anchor was inserted at the 5 o’clock of the glenoid rim in the right shoulder (7 o’clock in the left shoulder), and the suture was passed through the capsule. After shuttle-relay, a knot was secured on the capsular side of the labrum. In the same manner, the subsequent two or three anchors were inserted and secured in a row.

After surgery, the shoulder was held in an abduction brace for 4 to 5 weeks. A self-assisted circumduction exercise was initiated the day after surgery. Self-assisted passive ROM exercises were initiated as tolerated after removal of the brace. Self-assisted active ROM exercises were initiated eight weeks after surgery. Isotonic strengthening exercises with an elastic band were encouraged 3 months after surgery. The patients were allowed to return to their premorbid level of sports activities 6 months after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS ver. 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Student t-test was used to compare continuous or continuous ranked data, such as shoulder functional scores (SSV, Rowe, UCLA) and ROM between groups. Paired t-test was used to compare preoperative and postoperative values within each group. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical data such as presence of cyst and recurrence instability. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

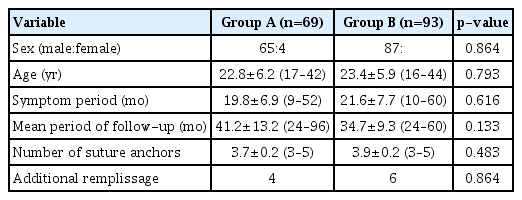

Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1, and there was no significant difference in any metric between the two groups. At final follow-up, the mean SSV, Rowe score, and UCLA shoulder score improved significantly in both groups: mean SSV improved from 40.1 to 93.2 in group A (p<0.001) and from 40.9 to 92.8 in group B (p<0.001); mean Rowe score improved from 46.1 to 91.6 in group A (p<0.001) and from 47.2 to 90.9 in group B (p<0.001); mean UCLA shoulder score improved significantly from 22.9 to 32.3 in group A (p<0.001) and from 23.5 to 32.5 in group B (p<0.001). There was no significant difference in these functional scores between the two groups (Table 2). During the study period, instability recurred in four patients (6%, 4/69) in group A and five patients (5%, 5/93) in group B, with no significant difference.

On preoperative 3D CT, the mean glenoid defect percentage was 15.6%±3.3% in group A and 14.9%±3.4% in group B. There was no significant difference between the two groups. On follow-up MRA/CTA, the incidence of peri-anchor cyst formation was 5.7% (4/69) in group A and 3.2% (3/93) in group B, with no significant difference.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study is to investigate clinical outcomes and radiological findings regarding cyst formation in the glenoid around suture anchors after arthroscopic Bankart repair with either biocomposite suture anchor or all-suture anchor in traumatic anterior shoulder instability. As we hypothesized, there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes including recurrence instability and incidence of peri-anchor cyst formation.

The bone reaction around the anchor is a complication after use of bioabsorbable anchors in the shoulder, and peri-anchor reaction has occurred in the glenoid after SLAP or Bankart repair as well as in the humeral head after rotator cuff repair [10,11,14]. Milewski et al. [11] reported bone replacement of biocomposite anchor in labral repair. In their study, 98% of anchor material was absorbed, 78% was replaced by soft tissue of variable density, and 20% was replaced by bone at 24 months after surgery. Three of 47 anchors (6.3%) showed peri-anchor cyst formation, which was similar to the incidence (7.2%) of the current study. Kim et al. [10] investigated the incidence of osteolysis and cyst formation after use of bioabsorbable anchors in rotator cuff repair. The incidence was 46.4% with variable grades of osteolysis, and they indicated that use of this bioabsorbable anchor should be reconsidered due to interference in revision surgery considering preservation of bone stock in the setting of adequate anchor resorption.

All-suture anchor was introduced in 2010 [15], to eliminate or reduce the concerns of bioabsorbable or biocomposite suture anchors, and recent studies underscored its clinical implications [15-17]. Although all-suture anchors have equivalent ultimate failure load to the traditional solid anchor system [18,19], Pfeiffer et al. [13] revealed in their in vivo study that these all-suture anchor system produced increased tunnel width and greater displacement under cyclic load. Tompane et al. [15] demonstrated that all-suture anchor yielded a low rate of cyst formation, and tunnel expansion greater than 80% was found in most patients at 12-month follow-up. However, this increased tunnel volume was not associated with clinical outcomes and recurrence instability. Lee et al. [16] compared the all-suture anchor with biodegradable anchor in arthroscopic Bankart repair and found that tunnel expansion was significantly greater in the all-suture anchor at 1-year follow-up, although it was not associated with clinical outcomes including recurrence instability during the study period. Similarly, the current study showed no significant difference in cyst formation (5.7% vs. 3.2%) at 6 month follow-up MRA/CTA or in clinical outcomes and recurrence instability.

Nakagawa et al. [20] raised the concern that cystic change and tunnel expansion in the glenoid might increase some unknown risk for anterior glenoid rim, especially in the setting of linear arrangement of multiple all-suture anchors. Although a large number of anchors was not always associated with glenoid rim fracture, they suggested that linear placement of suture anchors might induce weakness of the glenoid fossa and following glenoid rim fracture. Park et al. [21] reported similar cases of anterior glenoid rim fracture after arthroscopic Bankart repair. They used metal or bioabsorbable anchors and indicated that osteolysis around the suture anchor, especially without ceramic composite, might lead to rim fracture. In the current study, there was no glenoid rim fracture after Bankart repair.

There are several limitations to this study. First, this is a non-randomized retrospective study that has inherent selection bias for patient assignment. In the early study period, the biocomposite anchor was used, while the all-suture anchor was used later in the study. Second, the lack of significant difference in clinical outcomes might be due to the low statistical power resulting from the small number of patients. Third, we could not analyze tunnel expansion but only cyst formation because MRA was used in many cases. Fourth, follow-up MRA/CTA was performed 6 months after surgery, which may not be long enough to evaluate peri-anchor cyst formation.

In conclusion, considering the low incidence of peri-anchor cyst formation in the glenoid after Bankart repair with the two anchor systems and the lack of association with recurrence instability, both biocomposite and all-suture anchors in Bankart repair can yield satisfactory outcomes with no significant difference.

Notes

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

None.