Effects of steroid injection during rehabilitation after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair

Article information

Abstract

Background

This study aims to compare the clinical outcomes of steroid injections during the rehabilitation period after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ACRC).

Methods

Among patients who underwent ARCR, 117 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled. Pain and range of motion (ROM) recovery at the 3-, 6-, and 24-month follow-up visits and functional outcome at the 24-month follow-up were compared between 45 patients who received ultrasound-guided subacromial steroid injection at postoperative week 4 or 6 and 72 patients who did not. Functional outcome was assessed using the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score and Constant score. Healing of the repaired tendon and retear were observed at the 6-month follow-up via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) arthrography.

Results

At the 3-month follow-up, the steroid injection group showed lower visual analog scale scores than the control group (p<0.05) and showed faster recovery of forward flexion and internal rotation (p<0.05). From the 6-month follow-up, the two groups did not show differences in pain and ROM, and the ASES score and Constant score also did not significantly differ at the 24-month follow-up. The two groups did not differ in retear rate as determined by MRI or CT arthrography at the 6-month follow-up.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that ultrasound-guided subacromial steroid injection at 4 or 6 weeks after ARCR leads to quick pain reduction and ROM recovery until 3 months after surgery. Therefore, subacromial steroid injection is speculated to be an effective and relatively safe method to assist rehabilitation.

INTRODUCTION

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) is a minimally invasive surgical technique that enables a more accurate diagnosis of shoulder lesions and is associated with less postoperative pain and quick recovery of range of motion (ROM) compared to open surgical technique [1]. However, healing of the torn tendon is crucial for good clinical outcome after surgery. It is primarily associated with the patient’s preoperative characteristics, such as age, size of tear, muscle atrophy, and fatty infiltration, as well as postoperative rehabilitation [2,3]. To enhance the postoperative healing process, the shoulder joint should generally be immobilized for a certain period, and as a result, stiffness is one of the most common postoperative complications [4,5]. Stiffness after rotator cuff repair occurs as a result of adhesion of the articular capsule and surrounding soft tissues, which is in turn influenced by various factors, including preoperative stiffness, surgical technique, diabetes, and postoperative rehabilitation [1,6,7]. Rehabilitation is a critical factor in obtaining good postoperative clinical outcome. Although the most effective duration of immobilization and time to begin passive or active assisted exercise are still debated, postoperative pain is an important factor that hinders rehabilitation.

Due to their potent anti-inflammatory effects, corticosteroids have been frequently used for pain control and functional recovery, such as recovery of ROM. It is well known that intraarticular steroid injection reduces pain and promotes quick recovery of ROM by reducing synovial membrane inflammation and shoulder capsular fibrosis [8]. Subacromial steroid injection has been reported to produce the same effects in primary frozen shoulder [9]. Furthermore, the efficacy of steroids in controlling pain immediately after ARCR has been documented [10]. However, steroid injections in the shoulder joint have also been reported to accompany severe complications [11], and concerns with intraarticular steroid injection during the rehabilitation period persist due to the effects of steroids on the healing of the repaired tendon.

Therefore, this study aims to examine the effects of subacromial steroid injection on the effectiveness of rehabilitative exercise and healing of the repaired tendon in patients who underwent ARCR with limitation in rehabilitation due to pain at 4 or 6 weeks after surgery when they begin self-assisted passive range of motion.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (IRB No. NHIMC 2021-06-020). Informed consent was waived due to retrospective nature of this study.

One hundred ninety-eight patients who underwent ARCR between March 2014 and February 2016 at our hospital were retrospectively analyzed. The inclusion criteria were patients who received rotator cuff repair for a full-thickness tear or a partial tear involving more than 50% of the tendon that is practically irresponsive to conservative treatment. All surgeries were performed by one surgeon. The exclusion criteria were (1) patients who only underwent a partial repair due to the difficulty of a full repair, (2) patients with a history of surgery on the ipsilateral shoulder, (3) patients who did not receive computed tomography (CT) arthrography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 6 months after surgery, (4) patients who were not followed up for at least 2 years, and (5) patients who were involved in an industrial or traffic accident. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 117 patients were enrolled. Forty-five patients (38.5%) who received ultrasound-guided subacromial steroid injection at postoperative week 4 or 6 when the shoulder abduction brace is removed and assisted passive ROM is begun were classified into group A, and 72 patients (61.5%) who did not receive steroid injection were classified into group B for a retrospective analysis of the clinical and radiological outcomes.

All surgeries were performed arthroscopically in the lateral decubitus position under general anesthesia. During surgery, rotator cuff tears were classified into partial tear, small tear (<1 cm), medium tear (<3 cm), large tear, and massive tear (3–5 cm), and single row repair or suture bridge repair were performed accordingly. Postoperative pain was controlled using intravenous patient-controlled analgesia, and additional analgesics were administered when needed. All patients wore a shoulder abduction brace immediately after surgery, which was maintained until postoperative week 4 for patients with partial, small, and medium tears and postoperative week 6 for patients with large and extensive tears. Pendulum exercise was begun 1 to 3 days after surgery depending on the severity of postoperative pain, and assisted passive ROM exercise using a T-bar and pulley was begun at postoperative week 4 or 6 when the brace was removed. Assisted active ROM exercise was begun at postoperative week 8, and muscle strengthening training including forward flexion and internal and external rotation using an elastic band was begun at postoperative week 12. The patients were instructed to return to their preoperative activities or sports activity after 6 months of surgery.

Ultrasound-guided steroid injection was recommended to patients who complained of pain of visual analog scale (VAS) score 5 or higher at the postoperative week 4 or 6 outpatient follow-up, and the therapy was given to those who provided consent. A total of 5 mL of a mixture of 1 mL of triamcinolone (40 mg) and 4 mL of ropivacaine was injected to the superior of the repaired tendon while monitoring the status of the repaired tendon via ultrasound.

To assess clinical outcomes, pain (VAS score, 0–10) and ROM were measured for all patients before surgery and 3 months, 6 months, and 2 years after surgery. For a functional assessment, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score and Constant score were measured before surgery and 2 years after surgery. Passive ROM was measured. Forward flexion was measured while the scapula was immobilized, and external rotation of the arm was measured with the elbow fixed at the flank. Internal rotation was measured based on the highest level of spine the patient can touch with the ipsilateral thumb. For statistical analysis, the following numbers were given to the levels of spine: 1–12 for T1–T12; 13–17 for L1–L5, and 18 for the sacrum [12]. CT arthrography or MRI was performed at postoperative 6 months to verify whether the repaired tendon was healed.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Pain, ROM, ASES score, and Constant score between the two groups were compared with student t-test, and improvements of pain and functional indices within each group were examined by comparing preoperative and postoperative 2-year parameters using paired t-tests. Sex and tear sizes were classified using the chi-square test. Level of significance was set to p<0.05.

RESULTS

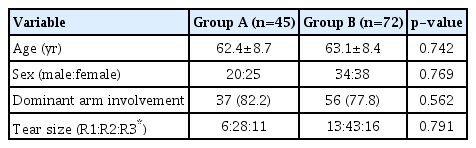

The mean age of group A (n=45), the group of patients who received ultrasound-guided subacromial steroid injection after surgery, was 62.4±8.7 years (range, 39–78 years), with 20 (44.4%) male patients. The mean age of group B (n=72), the group of patients who did not receive postoperative steroid injection, was 63.1±8.4 (range, 42–81) years, with 34 male patients. Thirty-seven patients (82.2%) in Group A and 56 patients (77.8%) in group B were operated on their dominant arm. In group A, the number of patients with partial tear, small and medium tear, and large and extensive tear were 6, 28, and 11, respectively, and the same for group B was 13, 43, and 16, respectively. The two groups did not significantly differ in their baseline parameters before surgery (Table 1).

The two groups did not significantly differ in preoperative pain as measured with VAS score, and both groups showed significant reductions in pain at the 2-year follow-up (p<0.05). At the 4- or 6-week follow-up, group A showed higher pain scores (5.9±1.1) than group B (4.4±1.5) (p<0.05). At the 3-month follow-up, group A showed a significant reduction in pain (2.1±1.2) compared to group B (3.1±1.1) (p<0.05). From the 6-month follow-up, neither group showed a statistically significant difference in pain (Table 2).

The two groups did not differ significantly in functional indices, as assessed with the ASES score and Constant score, before surgery. In group A, the ASES score and Constant score showed statistically significant improvement from 49.4±13.0 before surgery to 87.2±9.6 at the 2-year follow-up and from 56.5±10.4 before surgery to 86.4±7.8 at the 2-year follow-up, respectively. In group B, the ASES score and Constant score showed statistically significant improvement from 51.0±13.4 before surgery to 88.2±8.5 at the 2-year follow-up and from 57.3±9.7 to 84.9±8.1 at the final follow-up, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in the functional indices between the two groups at the 2-year follow-up (Table 2).

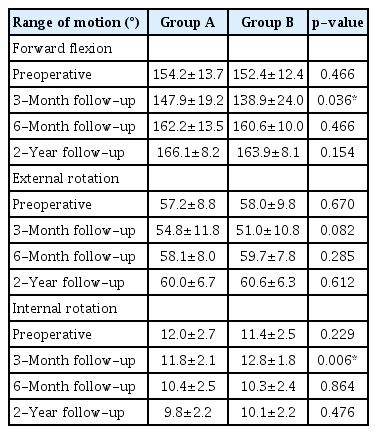

Forward flexion was not significantly different between the two groups before surgery, but it showed statistically significant higher angle in group A (147.9±19.2), which received steroid injections, than in group B (138.9±24.0), which did not receive steroid injections, at the 3-month follow-up (p<0.05). However, there were no differences between the two groups at the 6-month and 2-year follow-up visits. External rotation did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups before surgery and throughout the follow-up. Internal rotation did not significantly differ between the two groups before surgery, but group A (T12) showed statistically significant higher angles compared to group B (L1) at the 3-month follow-up. There were no differences at the 6-month and 2-year follow-up visits (Table 3).

CT arthrography or MRI performed at postoperative month 6 to verify the healing of the rotator cuff repaired tendon revealed that 24.4% (11/45) and 25.0% (18/72) of the cases in group A (steroid injection) and group B (no steroid injection), respectively, were re-torn, with no significant differences between the two groups.

DISCUSSION

Corticosteroids produce anti-inflammatory effects by reducing the production of arachidonic acid derivatives, such as prostaglandins or leukotrienes, by inhibiting phospholipase A2 [13]. For this reason, steroid injection has been used widely in shoulder-related problems to relieve pain or facilitate ROM recovery. The effect of intraarticular steroid injection on pain reduction and quick recovery of ROM in adhesive capsulitis has been documented extensively [9,14-17]. A prospective randomized study also demonstrated that subacromial steroid injection also produces the same effects in primary frozen shoulder [9]. Several studies have reported that subacromial steroid injection leads to quick pain relief and functional recovery in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome or rotator cuff tendonitis [18,19]. The clinical efficacy of steroid injection in degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint and full-thickness rotator cuff tear have been investigated [20,21].

Notwithstanding their efficacy in alleviating pain via anti-inflammatory actions, steroids are associated with multiple side effects. Intratendinous or intramuscular steroid injection can cause a tear by weakening collagen fibers [22]. Complications of shoulder joint steroid injections, such as tendon tears, have been reported in a few studies [20,23]. Watson [24] reported poor outcomes in rotator cuff repair in patients who received more than four steroid injections prior to surgery. Use of steroids immediately after surgery or during rehabilitation raises concerns for infection of the surgical site and may have adverse effects on the healing of the repaired tendon by inhibiting normal inflammatory reactions. However, steroid-related infections or problems with tendon healing on short-term follow-up were not observed in some studies that examined the use of multiple drugs, including subacromial steroid injection, for pain control immediately after surgery [10,25]. Shin et al. [26] administered subacromial steroid injection within 8 weeks of surgery on patients who complain of severe pain that keep them awake at night and reported that the retear rate at the 6-month MRI did not significantly differ between the steroid group and control group. In our study, steroid injection was performed 4 or 6 weeks after surgery—a period after the normal inflammatory reaction subsides—to minimize any complications of the steroid. Furthermore, injections were guided by ultrasound for all patients to prevent intratendinous and intramuscular injections and to minimize any damage on the repaired tendon. In addition, ropivacaine was chosen to administer with steroids for its relatively low cartilage toxicity and systemic complications [27]. In this study, we did not observe any complications of steroid injection, such as infection, and the steroid group did not significantly differ from the control group in the retear rate at the 6-month CT arthrogram or MRI after surgery.

Shoulder joint stiffness after rotator cuff repair is known to be caused by an inflamed shoulder capsule, as is in primary frozen shoulder, and surgery-related soft tissue adhesion, with incidence ranging from 4.9%–59% depending on the period [4,6,28,29]. This is one of the most important determinants, in addition to postoperative pain, of patient satisfaction [30]. The causes of postoperative stiffness have been reported to encompass age, diabetes, size of tear, extent of fat deposition, preoperative stiffness, surgical technique, prolonged postoperative immobilization, and the patient’s rehabilitation compliance [1,6,7]. Chung et al. [4] suggested an association with stiffness and VAS score at the 3-month postoperative follow-up. Shin et al. [26] reported that steroid injection during the rehabilitation period effectively reduced pain. However, they did not investigate whether pain relief is associated directly with recovery of ROM. Under the hypothesis that postoperative pain would have adverse effects on rehabilitation and eventually lead to stiffness, we administered steroid injections—only to the patients who provided consent after learning about the side effects—to patients with pain greater than VAS 5 at postoperative week 4 or 6, when the shoulder abduction orthosis is removed and assisted passive ROM exercise is begun. At the time of injection, the steroid group had a higher VAS score than the control group, but not to a statistically significant degree. At the 3-month follow-up, the steroid group had a lower VAS score and showed faster improvement of forward flexion and internal rotation in measurement of ROM. In this study, at 3 months follow-up, the angle difference between the two groups was 9°, and the internal rotation was measured as the difference in spine 1 level. Although this is statistically significant, it is a place where errors can occur due to differences in actual measurements since it is not a value that exceeds 20°, which is the minimal clinical difference in the literature. However, in group A, where postoperative pain was severe, there was a dramatic decrease in pain at follow-up 1.5 to 2 months after steroid injection. This is evidence to support the higher angle measurement at 3 months after surgery. Such quick recovery of ROM may be attributable not only to the direct effects of steroid injection in primary frozen shoulder, such as inhibition of synovial proliferation and fibrosis [8], but also to the indirect effects where reduced pain leads to compliance with rehabilitation.

This study has a few limitations. First, the small population size, retrospective design, and non-randomization of the experimental and control groups may induce bias when drawing inferences regarding the direct causal relationship between steroid injection and ROM recovery. Furthermore, the follow-up period was relatively short, hindering us from surveying the long-term effects of the steroid. Nevertheless, this study is meaningful as the first report to analyze the relationship between steroid injection during rehabilitation and ROM recovery during follow-up.

This study demonstrated that ultrasound-guided subacromial steroid injection at 4 or 6 weeks after ARCR leads to quick pain reduction and ROM recovery until 3 months after surgery and that the steroid and control groups did not differ in retear rate at the 6-month follow-up. Therefore, subacromial steroid injection during the rehabilitation period after ARCR may be an effective and relatively safe method of facilitating rehabilitation.

Notes

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

None.