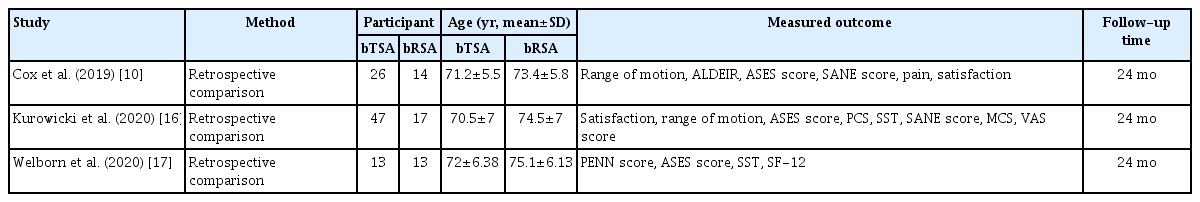

Bilateral reverse shoulder arthroplasty versus bilateral anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: a meta-analysis and systematic review

Article information

Abstract

As the population is aging and indications are expanding, shoulder arthroplasty is becoming more frequent, especially bilateral staged replacement. However, surgeons are hesitant to use bilateral reverse prostheses due to potential limitations on activities of daily living. This meta-analysis was conducted to compare bilateral anatomic to bilateral reverse shoulder implants. PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar (pages 1–20) were searched until April 2023. The clinical outcomes consisted of postoperative functional scores (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [ASES], Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation [SANE], Physical Component Score [PCS], Mental Component Score, and Simple Shoulder Test), pain, and range of motion (external rotation and forward elevation). Three studies were included in this meta-analysis. Bilateral anatomic implants had better postoperative functional outcomes and range of motion, but no significant difference was seen in postoperative pain when compared to the reverse prosthesis. Better ASES score, SANE score, and PCS as well as better external rotation and forward elevation were seen in the bilateral anatomic shoulder replacement group, but no significant difference in pain levels was seen between the two groups. These results may be explained by the lower baseline seen in the reverse prosthesis group, which may be due to an older population and different indications. Nevertheless, more randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm these findings.

INTRODUCTION

In unilateral shoulder disease, anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) are both viable therapy choices for end-stage arthropathy. For patients with severe glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA), TSA has shown improved functional outcomes [1,2] and good long-term survivability [1,3]. RSA has also shown excellent outcomes [4-6].

Every year, more TSA and, in particular, RSA procedures are carried out [7]. There are several factors contributing to the rise in RSA, such as growing indications, like its usage in revision shoulder arthroplasty, posterior glenoid bone loss, and fracture sequelae [8,9]. Patients now frequently need staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasties due to a rise in the incidence of shoulder OA and rotator cuff illness, increased life expectancy, and the expansion of indications [10]. The influence on activities of daily living (ADLs), particularly the upkeep of perineal cleanliness, has historically been one concern of bilateral RSAs (bRSAs). However, new research indicates that people with bRSAs can still carry out these tasks to a satisfactory level [11-14].

A lot of studies have compared unilateral anatomic and RSA, however, there is still not enough evidence regarding bilateral replacements. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to compare the patient-reported outcomes of bilateral anatomic to RSA. Our hypothesis is that patients undergoing bilateral anatomic will have better outcomes than those undergoing bRSA.

METHODS

Search Strategy

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. PubMed, Cochrane, and Google Scholar (pages 1–20) were searched up until April 2023 (using the following keywords and Boolean terms “Arthroplasty” OR “Replacement” OR “Prosthesis” AND “Shoulder” AND “Bilateral”) for qualified studies in order to compare bilateral TSA (bTSA) to bRSA. Literature was also identified by tracking reference lists from papers and Internet searches. One investigator (MD) extracted the data, and another investigator (MYF) confirmed the choice of articles. The process is summarized in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart for article selection.

Inclusion criteria were (1) comparative studies: randomized controlled trials, retrospective comparative studies, and prospective clinical trials; (2) patients who had bilateral shoulder replacements; and (3) bTSA used in one group and compared to another group where bRSA was used. Studies with the following characteristics were excluded from this study: (1) case reports, narrative or systematic reviews, theoretical research, conference reports, meta-analyses, expert comments, and economic analyses; (2) non-relevant outcomes; and (3) studies including simultaneous (instead of staged) bilateral shoulder replacements.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers determined the eligibility of the studies independently. Extraction of the analyzed data was made from the included studies and consisted of two parts. The first part comprised basic information containing names of authors, title, publication year, journal, volume, issue, pages, study design, sample size along with the size of each group of management, and different types of bias suspected in each study. The second part consisted of the clinical outcomes, which were the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) score, the Physical Component Score (PCS), the Mental Component Score (MCS), the Simple Shoulder Test (SST), the visual analog scale (VAS), external rotation (ER), forward elevation, and adverse events. Any arising difference between the investigators was resolved by discussion.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The ROBINS-I tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions was used independently by two writers (MD and MYF) for each manuscript [15]. Studies that had a critical risk of bias were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

For articles with missing data, their authors were contacted to provide it. The statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020). For continuous data, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and standardized mean differences were utilized, while risk ratio with 95% CI was used for dichotomous data. Q tests and I2 statistics were used to evaluate heterogeneity indicating considerable heterogeneity if P ≤0.10 or I2 > 50%. High levels of variability in the variables were handled by the random-effects model and the fixed-effect model was chosen if p>0.10 or I2 < 50%. A statistically significant result is shown by P=0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Included Studies

Only three studies [10,16,17], which are retrospective, met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. It involved 86 subjects in the bTSA group and 43 subjects in the bRSA group. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. The results of the bias assessment for non-randomized studies are summarized in Table 2.

Functional Outcomes

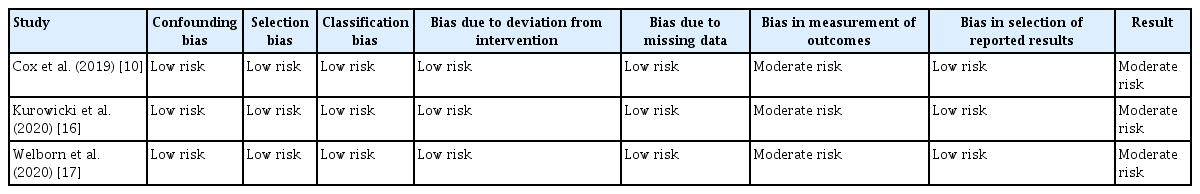

ASES score

Three studies on 129 subjects (86 bTSA and 43 bRSA) reported data on postoperative ASES scores. When compared to bRSA, bTSA showed better improvement in ASES score postoperatively (mean difference, 8.96; 95% CI, 3.94–13.98; P=0.00005) (Fig. 2A).

(A) Forest plot of the postoperative American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score in bilateral reverse shoulder arthroplasty (bRSA) and bilateral total shoulder arthroplasty (bTSA). (B) Forest plot of the postoperative Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation score in bRSA and bTSA. (C) Forest plot of the postoperative Physical Component Score in bRSA and bTSA. (D) Forest plot of the postoperative Mental Component Score in bRSA and bTSA. (E) Forest plot of the postoperative Simple Shoulder Test score in bRSA and bTSA. SD: standard deviation, IV: inverse variance, CI: confidence interval.

SANE score

Two studies on 103 subjects (73 bTSA and 30 bRSA) reported data on postoperative SANE scores. The results indicated that when compared to bRSA, bTSA showed better improvement of SANE score postoperatively (mean difference, 13.06; 95% CI, 5.64–20.48; P=0.00006) (Fig. 2B).

PCS

Two studies on 90 subjects (60 bTSA and 30 bRSA) reported data on postoperative PCS scores. When compared to bRSA, bTSA showed better improvement of PCS score postoperatively (mean difference, 6.95; 95% CI, 1.53–12.36; P=0.01) (Fig. 2C).

Mental Component Score

Two studies on 90 subjects (60 bTSA and 30 bRSA) reported data on postoperative MCS scores. The results demonstrated no statistically significant difference between bRSA and bTSA (mean difference, –0.77; 95% CI, –4.45 to 2.92; P=0.68) (Fig. 2D).

Simple Shoulder Test

Two studies on 90 subjects (60 bTSA and 30 bRSA) reported data on postoperative SST scores. The results showed no statistically significant difference between bRSA and bTSA (mean difference, 0.61; 95% CI, –0.59 to 1.8; P=0.32) (Fig. 2E).

Visual Analog Scale

Two studies on 103 (73 bTSA and 30 bRSA) subjects reported data on postoperative VAS. The results indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between bRSA and bTSA (mean difference, –0.31; 95% CI, –1.04 to 0.4; P=0.39) (Fig. 3).

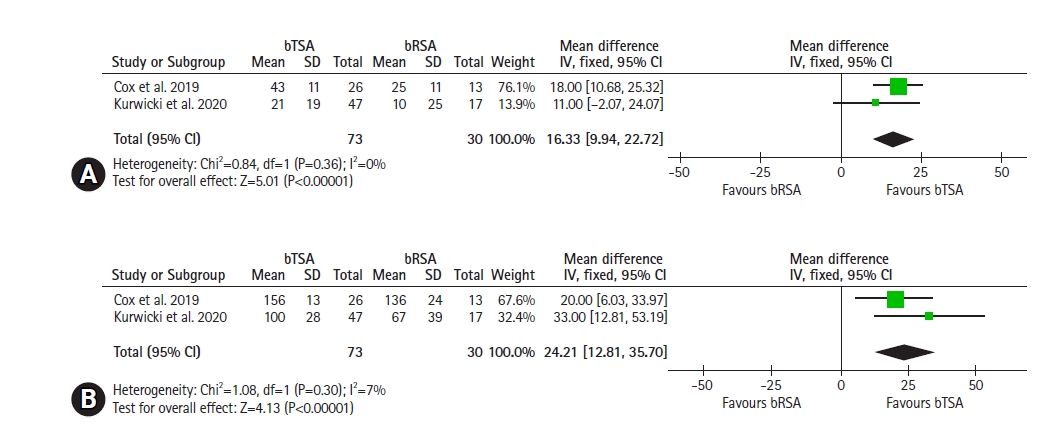

Range of Motion

Two studies on 103 subjects (73 bTSA and 30 bRSA) reported data on postoperative range of motion (ER and forward elevation). When compared to bRSA, bTSA led to better improvement of ER (mean difference, 16.33; 95% CI, 9.94–22.72; P<0.00001) (Fig. 4A) and forward elevation postoperatively (mean difference, 24.21; 95% CI, 12.72–35.7; P<0.0001) (Fig. 4B).

Adverse Events

Two studies on 65 (39 bTSA and 26 bRSA) subjects reported data on postoperative adverse events. The results showed no statistically significant difference between bRSA and bTSA (odds ratio, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.24–5.03; P=0.90) (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

Our most important findings included a significantly greater benefit of bTSA when compared to bRSA in terms of postoperative ASES score, SANE score, and PCS as well as postoperative ER and elevation. In fact, due to the higher number of shoulder OA and other pathologies, both anatomical and reverse prosthesis shoulder replacements are increasing in number. Furthermore, staged bilateral shoulder arthroplasty is becoming more frequent. However, surgeons hesitate to perform bRSA, fearing that the procedure may impact ADLs. There are not enough data comparing bRSA to bTSA which is why this meta-analysis is comparing both replacements.

Our results showed higher postoperative ASES score, SANE score and PCS in bTSA when compared to bRSA. However, another study comparing bRSA to bTSA showed that even though the latter had better postoperative functional outcomes, the difference between the pre- and postoperative scores was not significantly different [16]. Higher postoperative functional scores in bTSA might be explained by the higher baseline function, which may be a result of the different indications in the analyzed studies, such as the presence of OA in the bTSA group or the presence of rotator cuff tear arthropathy or TSA revision in the bRSA group [10,16-18], and the older age of patients receiving bilateral reverse implants [10,16,17]. In fact, there was no difference in postoperative pain or adverse events between these two implants and studies have reported similar levels of satisfaction [10,17].

BTSA showed better postoperative ER and forward elevation than bRSA. However, this may also be attributed to the lower baseline range of motion in the bRSA group, which can explain the absence of a difference in pre- to postoperative changes in ER and forward elevation between groups [16]. In fact, surgeons hesitate to perform bRSA in combination because of the potential impacts on ADLs due to the limitation in internal rotation. Nevertheless, a study by Kurowicki et al. [16] showed that the bRSA group had greater improvement in internal rotation than the bTSA group. Other studies have also shown normal management of ADLs and independence in maintaining personal hygiene after staged bRSA [10-14]. To ensure better external and internal rotation in bRSA, surgeons can use a reverse shoulder prosthesis with a lateralized center of rotation, as shown by a systematic review that demonstrated a better range of motion with this prosthesis as well as an improvement in ASES scores [19].

This study has several strengths: It is the first meta-analysis comparing bTSA to bRSA. Moreover, only comparative studies were included, reducing the risk of operative and matching bias. This makes the study less heterogeneous and decreases the risk of bias. However, this study also had limitations: There were not that many comparative studies in the literature to include; inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients varied; and the data used for analysis were pooled so individual patients’ data were unavailable, which could limit more comprehensive analyses. Furthermore, even though we were able to report a statistically significant difference in functional scores, we were not able to determine whether this difference reached the minimal clinical important difference. Moreover, in the range of motion analyses, there was no sufficient data to analyze the internal rotation.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first meta-analysis comparing bTSA to bRSA. bTSA led to better ASES score, SANE score and PCS as well as a better range of motion. However, these results may be biased by higher pre-operative baseline scores due to the younger population in the bTSA group and different indications, such as rotator cuff tear arthropathy in the bRSA group. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in postoperative pain levels, adverse events, or levels of satisfaction between the two groups. There was also no limitation of ADLs in the bRSA group. In terms of clinical impact, bTSA appears better than bRSA in patients requiring bilateral shoulder replacement. Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted carefully due to the limited number of included studies and different indications for each type of surgery and, therefore, different baseline function. Thus, more randomized controlled studies analyzing changes between baseline and the postoperative period are needed to confirm these results.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JA. Data curation: MYF, JK, JS. Formal Analysis: MD, JK, JS. Supervision: JA. Writing – original draft: MD, MYF, JS. Writing – review & editing: MD, JA.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Data availability

None.

Acknowledgments

None.